Fg Off. Niels Erik Westergaard

(1922 - 1944)

Profile

Niels Erik Westergaard joined the Royal Air Force in 1941 and trained as Navigator. He was killed in action on 2 January 1944 during a raid on Berlin. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously.

Niels Erik Westergaard was born in Wandsworth, England, on 25 July 1922. He was the son of a Danish constructional engineer, Otto Ludvig Blædel Westergaard, who had moved to England in 1919 to start a successful career. Two years later he married Westergaard’s mother, Inger Westergaard (nee Nyrup), in Copenhagen. The family lived in London apart from five years in Teheran in 1934-39. Westergaard’s parents divorced in the late 1930s, however, and his mother, younger brother and sister moved to Denmark. Westergaard, then aged 16, remained in England to finish school.

Westergaard was British subject by birth. However, as he was born to Danish parents abroad, according to Danish nationality law he was considered Danish until the age of 22.

Westergaard volunteered for the Oxford University Air Squadron in 1940 and from early 1941, in addition to academic studies at Oxford, he was trained according to the Royal Air Force syllabus. He joined in Royal Air Force Voluntary Reserve and continued training as navigator in Canada from late 1941. On 1 December 1942, he was commissioned as Pilot Officer (133578, RAFVR).[1] He returned to England and—presumably—he was posted to an Operational Training Unit (OTU).[2]

On 1 June 1943, he was promoted to Flying Officer and, two weeks later, he was posted to 619 Sqn. This fairly new squadron had been established at RAF Station Woodhall Spa in April 1943. Westergaard was posted as the navigator of Fg Off. D. A. MacDonald’s (J.14619) crew from 1660 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at RAF Station Swinderby. The other members of the crew were: Sgt Smale (F/E), Plt Off. J. Heedlam (W/Op), Sgt. Forrester (A/G), and Sgt. Meegham (A/G).[3]

Into Battle

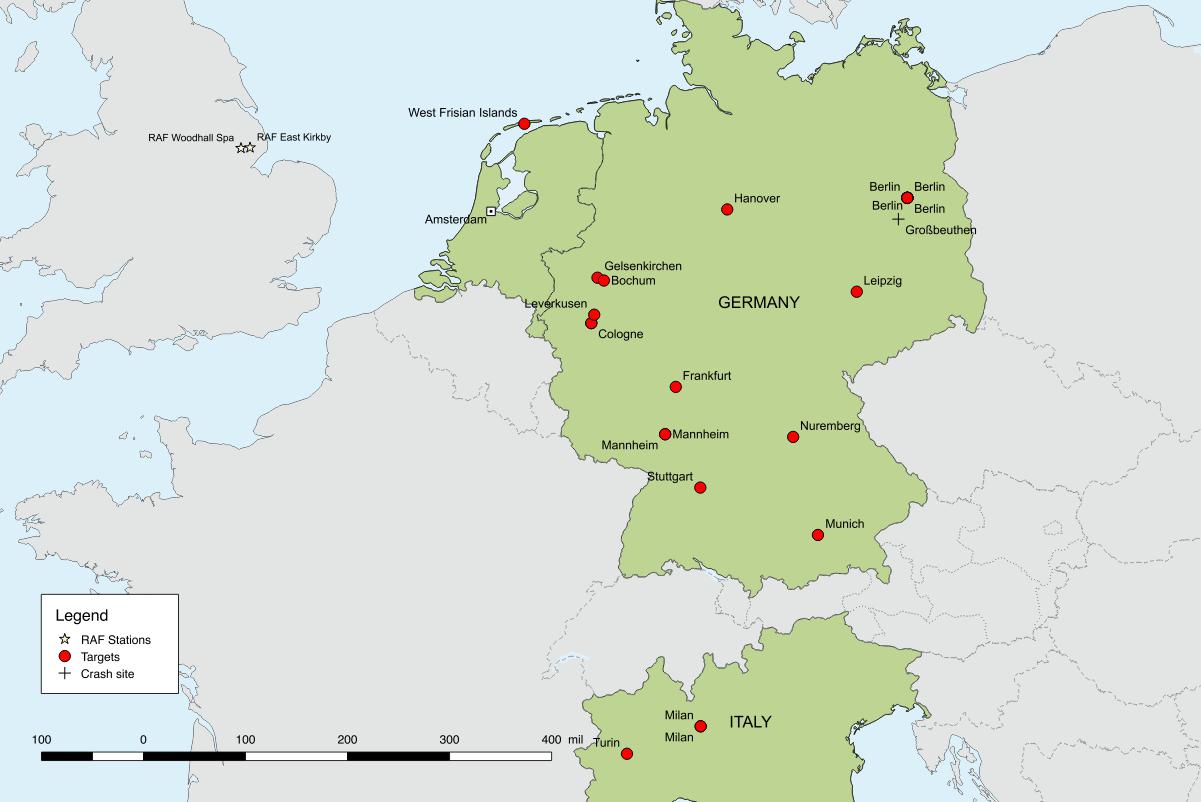

Westergaard entered operational service in the final stages of the five months strategic bombing campaign against the German industrial Ruhr area, the Battle of the Ruhr. This was the first campaign in a period—early 1943 to early 1944—which AOC-in-C AM Sir Arthur Harris later described as Bomber Command’s main offensive.[4] Within the next six months, Westergaard would take off on twenty-five sorties of which the majority were deep into Germany including no less than eight for Berlin. Westergaard’s first operation—a gardening (mining) operation on 1/2 July 1943 off the West Frisian Islands (Nectarine I area)—was the odd one out.

Three days later, the target was Cologne. Bomber Command carried out three major raids on Cologne in late June/early July. Westergaard participated in the last two of these raids. Lancaster B III EE116/PG-Q took of from Woodhall Spa at 2307 hours joining more than 650 other aircraft in the raid. Arriving over the target area, the town was partly covered by cloud, but they managed to identify the target easily. The crew bombed at 0158 hours and as they left the target area, the city seemed to be one big fire. They were able to see the fire from a distance of 200 miles on the return journey. Westergaard’s crew returned to Cologne on 8/9 July 1943 in another successful attack on the city. Cologne was hit hard in the three attacks this summer. A large number of industrial areas and houses were destroyed, many civilians were killed and more than 350,000 civilians became homeless.[5]

Further operations over Germany followed in the weeks to come: Gelsenkirchen on 9/10 July, Nuremberg on 10/11 August and Leverkusen on 22/23 August 1943.

Italy

The Allies invaded Sicily on 10 July 1943 (Operation Husky) setting off the Italian campaign. Two days later, Westergaard participated in an attack on Turin in Northern Italy, and he returned to the area twice during the following month. In response to urgent political orders, Bomber Command carried out a number of attacks on Northern Italy in August in order to hasten an Italian surrender. Westergaard participated in attacks on Milan on 7/8 and on 15/16 August. The crew successfully identify the target during both raids. During the latter operation, the German night fighters were very active. Westergaard’s crew reported that ‘The Germans appeared to have the route taped and were waiting all along the way.’[6] On ground the crew observed large fires developing and a large column of smoke from the northern end of the city. Italy surrendered on 8 September 1943 only days after the Allied landings on mainland Italy (Operations Avalanche, Baytown and Slapstick).

Berlin

Bomber Command returned to Berlin in August, launching three major attacks from 23/24 August to 3/4 September on the German capital. Westergaard’s crew was detailed to participate in two of these attacks. During the first raid, on 31 August, they had to abort the operation over the Dutch coast, though. Three days later, the crew had more luck. They reached Berlin and bombed what they believed to be the target. The markers had been dropped short of the target, which indicate that the crew’s bombs did not hit the actual target. The general results of these August raids were disappointing to Bomber Command, especially taking into consideration the heavy losses. Therefore, AM Harris decided not to direct major attacks on Berlin for the next two months. From mid-November 1943 to March 1944, Berlin became the most important target for Bomber Command.

During September and October a number of other targets were attacked. Westergaard participated in attacks on Mannheim (on 6/7 and 23/24 September), Bochum (on 29/30 September), Munich (on 2/3 October), Stuttgart (on 7/8 October), Hannover (on 18/19 October) and Leipzig (on 20/21 October).

The raid on Leipzig turned out to be a challenge. First of all, the weather was very bad both en route and over the target. Leipzig was covered by cloud and there were severe icing conditions. Secondly, all the navigational aids as well as the Lancaster’s rear turret became unserviceable, while the port outer engine failed. Westergaard had to demonstrate everything that he had learned in order to navigate the Lancaster (JA867/PG-X) back to England. This accomplishment was a major part of the citation, when he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross post mortem in January 1944.

As navigator, Flying Officer Westergaard has participated in many successful sorties against the enemy. In October, 1943, he was detailed to take part in an attack at Leipzig. During the flight all the navigational aids, including compasses, became unserviceable but, with no knowledge of the airspeed being maintained Flying Officer Westergaard, with outstanding skill and courage, navigated his aircraft back to this country. Throughout his operational tour, this officer has displayed a fine fighting spirit and devotion to duty of the highest order.[7]

630 Squadron

On 15 November 1943, 630 Sqn was established at RAF Station East Kirby in Lincolnshire. The nucleus of the new squadron was the ‘B’ Flight of 57 Sqn, but a number of crews were posted to the squadron from other units. One of these was the MacDonald crew, including Westergaard, who was posted on the 16th. The crew did not have much time to settle at their new squadron. Two days later, on 18/19 November, they were detailed for the first of a number of raids on Berlin. The real air Battle of Berlin had begun. Westergaard returned to Berlin again on 22/23 November, 23/24 November, and 2 December. Following a single operation on Frankfurt on 20 December, they were detailed for operations on Berlin once again on 29 December and 1 January 1944. The latter operation became the crew’s last.

The Last Mission

The operation on New Year’s Day had been planned to begin in the early evening originally, but uncertainty about the weather delayed the operation until midnight. The delay meant that the planned route over Denmark and the Baltic Sea and returning over Ruhr and Belgium had to be changed. Instead of the more direct and shorter route over the Netherlands had to be used; German night fighters had been very active in this area during previous attacks.

The Lancaster (JB532) took off at 2355 hours captained by Flt Lt MacDonald, DFC. Sqn Ldr K. F. Vale, AFC, flew as second pilot on the mission. It was quite usual for rookie pilots to fly as second pilot to a more experienced pilot before taking off on their own. However, Sqn Ldr Vale’s rank and merits could indicate that he came along as an observer rather than as a rookie. Nothing was heard from the aircraft after take off.[8] It was not until after the war that the circumstances of the crass became clear. A crash investigation report dated 20 March 1947 and compiled at No. 21 Section, No. 4 Missing Research & Enquiry Unit, RAF, states that

One the night of 31st Dec 43/1st Jan 44 between midnight and 0100 hrs a four engined aircraft was shot down by FLAK on returning from BERLIN and flying in the vicinity of GROSS BEUTHEN. One engine was shot off and it fell away from the aircraft. The aircraft did not catch fire but crashed diving steeply about 300 yds North West of the village. According to the eye-witness no one baled out and the entire crew perished in the crash.

Two bodies were found in the middle of the fuselage and six others were found scattered around the wreckage. All the bodies were badly battered but not burnt.[9]

Even if the date and time of the crash indicated in the report are not correct, it is clear that JB532 was shot down by flak and crashed in the vicinity of the town of Großbeuthen approximately 20 miles south-west of Berlin. Furthermore, none of the crew members and that the entire crew was killed. They were buried in a small cemetery near the town and with neither religious service nor military honours.[10] The bodies were transferred to the military cemetery in Berlin after the war, where the graves remain to this day.[11]

The Battle of Berlin continued until March 1944. Nearly 30,000 tons of bombs were dropped in more than 9,000 sorties. Losses were high. JB532 was one of approximately 500 aircraft and Westergaard one of nearly 2,700 aircrew lost in the battle.[12]

Endnotes

[1] London Gazette, 35930, 5.3.1943.

[2] Private correspondence with the Westergaard family.

[3] NA: AIR 27/2131.

[4] Harris et al., 2014.

[5] Middlebrook and Everitt, 2011.

[6] NA: AIR 27/2131.

[7] London Gazette, 36810, 21.11.1944.

[8] NA: AIR 27/2131.

[9] NAA: A705, 166/36/169, p. 14-17.

[10] NAA: A705, 166/36/169, p. 14-17.

[11] www.cwgc.org.

[12] Delve, 2005; Middlebrook, 2010.

Bibliography

Harris, A. T. et al.(2014). Bomber Harris: Sir Arthur Harris’ despatch on war operations 1942-1945. Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

Middlebrook, M. (2010). The Berlin Raids : The Bomber Battle, Winter 1943-1944. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation.

Middlebrook, M., & Everitt, C. (2011). The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book, 1939-1945. Hinckley: Midland.