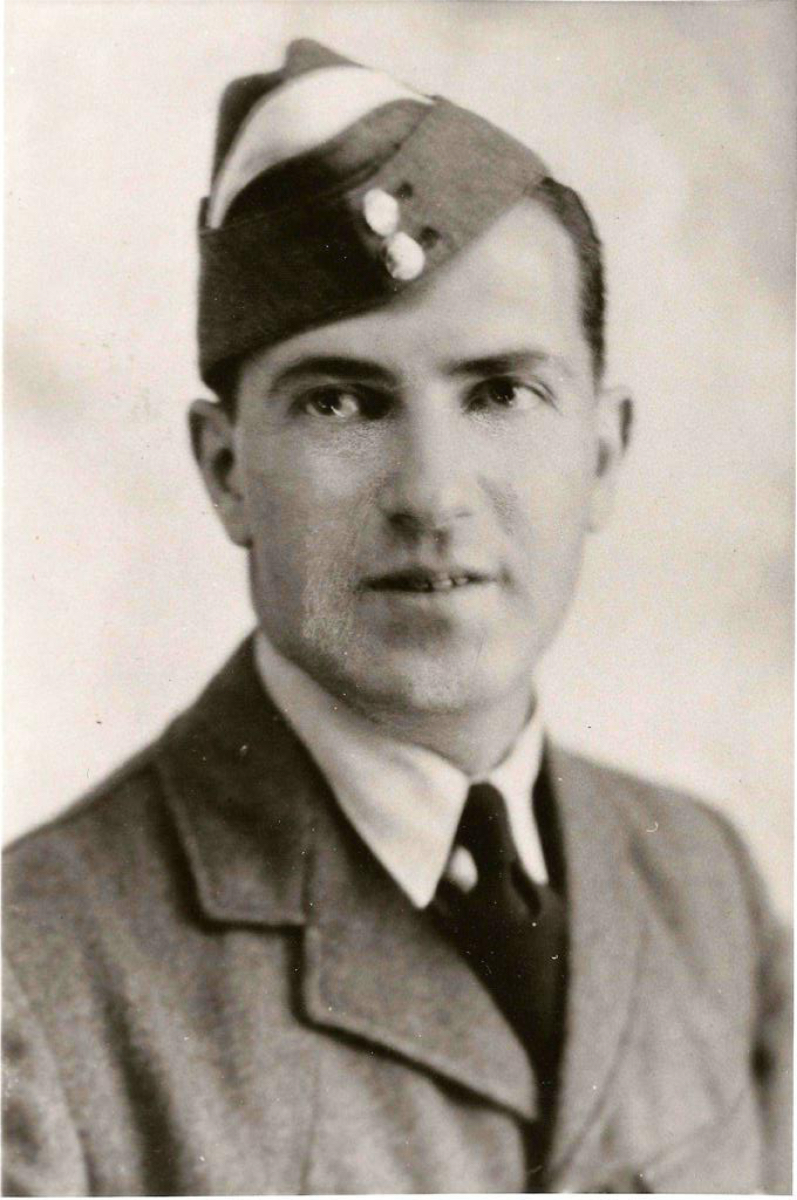

Jørgen Tage Bruun

(1911 - 1987)

Profile

Fg Off. Bruun was in London in 1940 to buy goods for Magasin du Nord, a Copenhagen department store. He was exiled by the German occupation of Denmark, and volunteered for the RAF in 1942. He served in the Far East and returned Denmark in 1945.

Jørgen Tage Bruun was born on 2 Juli 1911 in Frederiksberg, the son of traveling salesman Arthur Axel Bruun and Gella Jeanette Bruun (née Levy).[1] He completed military service in the Royal Guards in 1932, and promised himself never to wear a uniform again on a voluntary basis.[2] Bruun lived in the United Kingdom for a year in 1937 as part of his commercial training. During the day he worked in a store, and in the night he followed courses at the business college. The first six months he was a volunteer at Harrods in London and, later, he worked in Scotland. During this year, he made contacts which would later prove to be very important.

Exiled

Bruun was working in Magasin du Nord, one of the leading Copenhagen department stores, before the war. After the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, the men’s department was running out of stock as people were hoarding. Therefore, Bruun was sent to London to buy new supplies on 20 March 1940. On 9 April, while he was preparing to return to Copenhagen three days later, he learned about the German invasion. At first, he could hardly believe the news, and reality only dawned upon him as the newspapers and radio broadcasted details on the events. He went to the Danish Legation in Pont Street in search of information on how to react, but the Legation was not able to help. He decided to stay in London and volunteer for military service in either the British or the Norwegian forces. This proved to be more difficult than he had realised. Two years would pass before he commenced training in the RAF.[3]

Exiled from home, Bruun had to find a way to earn a living. His contacts at Harrods proved valuable and as soon as he had obtained his work permit, on 1 July 1940, he started working here. However, the staff council opposed the employment of foreigners in the store, and Bruun’s stay at Harrods became shorter than expected. The management got him a position at Rowan & Co., a department store in Glasgow. Four months would pass, before the work permit had been transferred to Scotland.

During the four months, Bruun experienced the first blitz in London. One of the episodes Bruun later remembered was watching the dog fighting in the air over Lord’s Cricket Ground, where he attended a match on 7 September 1940. Many years later, he still remembered another spectater saying: ‘What a pity they don’t have different colours, so we could follow the score.’ A few months later, a German fighter strafed the Kingston Bridge in Kingston-upon-Thames, as Bruun and a fried passed. Bruun decided to join the RAF, and not other branched of the armed forces, following this episode.

Bruun received notice from the RAF in the fall of 1941, that they had begun accepting foreigners, including Danes, for service. He was told that it would last several months before enlistment and, during this time, he attended evening courses in navigation and mathematics to prepare.[4]

In May 1942, Bruun visited the Lord’s Cricket Ground once again, however, this time it had been converted into a recruitment centre. He received his basic training at the RAF training depot in Ludlow in Shropshire and later he moved on to 1 Initial Training Wing ("C" Flight, 1 Squadron) in Stratford-on-Avon. Bruun was accepted for pilot training, but in the end was found to be too old for further service training. Instead, he was posted to South Africa to be trained as an air bombardier.

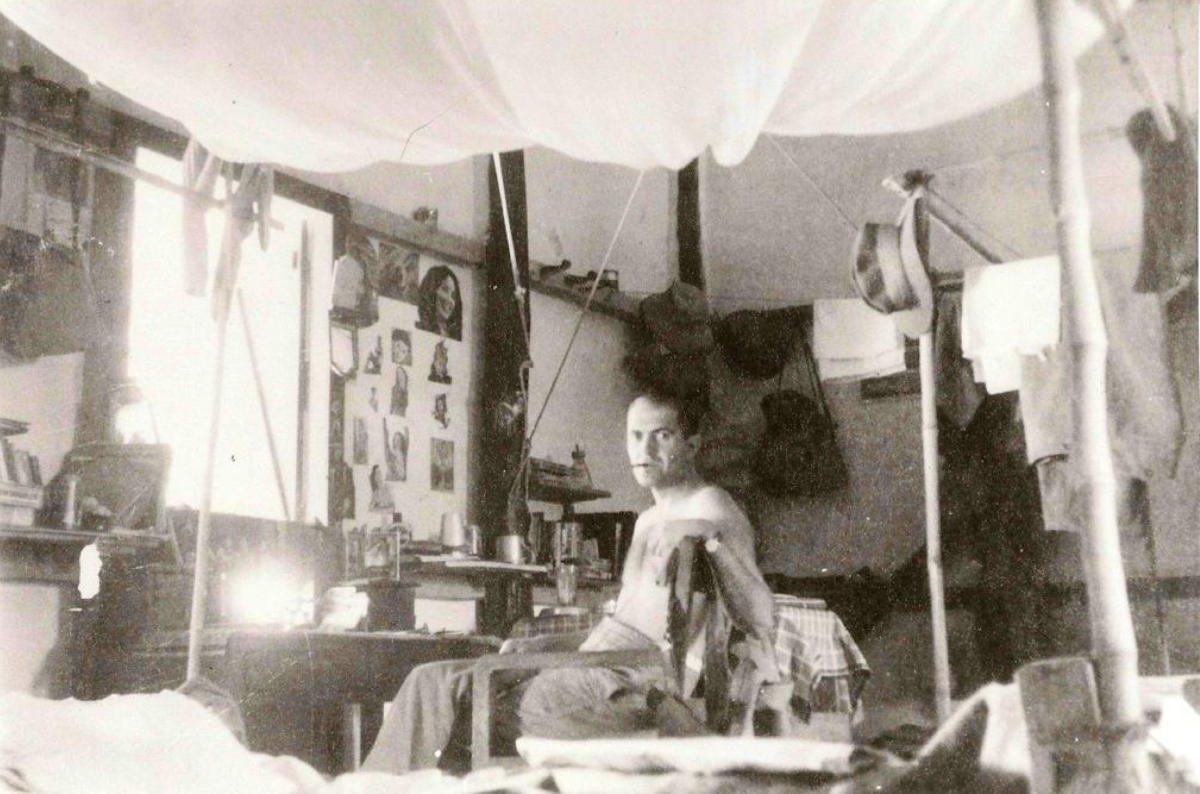

Bruun returned to England in the spring of 1944, hoping to take part in the expected invasion in Northern France, but he soon realised that crews for this operation had long been trained. As the first troops crossed the beaches of Normandy, Bruun found himself on a ship headed for Port Said in Egypt. Here he was to train for the invasion of Southern France. A few days after its arrival at Port Said, the troop ship received new orders and headed for Bombay. Following a short leave in Bombay, Bruun and the other aircrew travelled for five days through India to RAF Salbani, about 200 miles north-west of Calcutta, the home of 356 Squadron.

Defending an Empire

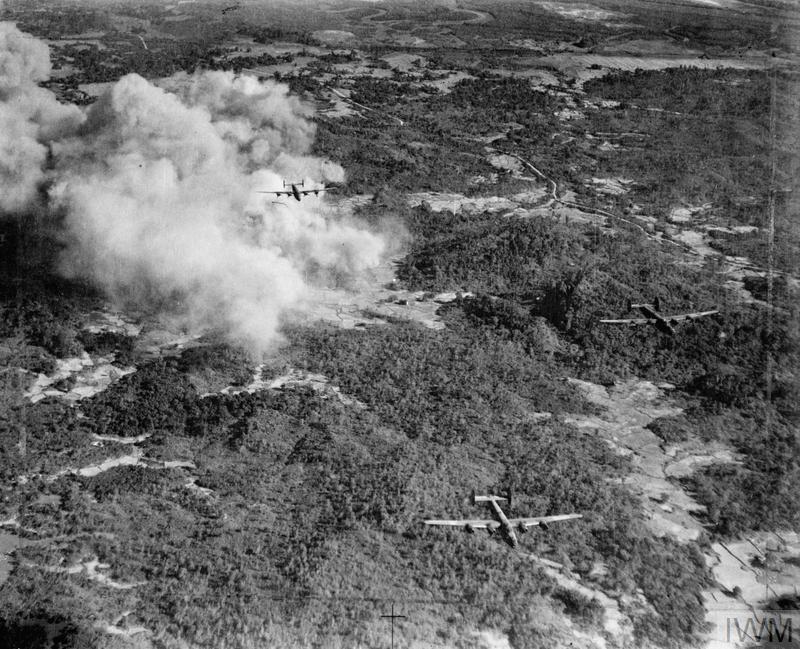

Bruun arrived in India on posting to 356 Squadron, which was part of the Strategic Air Force. The Strategic Air Force in South-East Asia was very small in comparison to the air forces in Europe; the RAF contingent consisted of four Liberator squadrons, 99, 292, 255, and 356 Squadrons.[5]

For the next ten months, Bruun was involved in more than thirty raids against targets in Burma, Siam (Thailand), and on the Malaysian peninsula all the way to the southernmost point, Victoria Point, where the Japanese had crossed the border in their initial invasion of Burma in January 1942.[6]

After the war, Bruun noted that he could not help but be disappointed at not being posted to Europe, which he then believed to be the focal point of the war. Instead, he was forced to make an effort in as remote a front as India—only later it became clear to him that he was as much needed in India as in Europe.[7]

‘The weather was the primary enemy’

Bruun flew nine missions during October and November 1944. The main objective of the Strategic Air Force at this point was to disrupt the Japanese communication lines in Burma: therefore, Bruun was part of a number of operations against the Burma–Siam railway. It is estimated that 13,000 prisoners of war and 80–100,000 civilians died during the construction of the railway. At least two Danes—H. Madsen and T. Lunøe, former employees at the Ulu Bernam estate—participated in the work as prisoners of war.

In early October 1944, low clouds and torrential rain prevented flying operations. On 6 October, the weather had improved enough to allow Bruun’s first operational mission, the target being the railway between Bangkok and Chieng Mai. Prior to the operation, the squadron had been practising low level attacks on railroad targets.[8] The targets of this operation were locomotives and trains between Phitsanulok and Nakhon Sawan in Siam, a section of about 60 miles. Bruun’s first operation proved to be a tough ride. Liberator Mk. VI KG971/G, piloted by Tucker (1554259, RAFVR), took off in a group of eight aircraft and set course for the railway. South of Phitsanulok, the leading aircraft sighted a train and attacked from low altitude. Bruun’s aircraft was flying as number two during the attack. The aircraft followed the railway line south and attacked a railway bridge at Paknam Poh, but the bombs overshot and fell in the water. ‘It was not perfect, but most bombs hit the target, and I returned with some good photos,’ Bruun later remembered.[9] The crew then headed back to base. While underway, they encountered very bad weather, having to fly through a thunderstorm. They returned to base after nine hours of very difficult flying, grateful to be alive. It was experiences like this that later on made Bruun state that the weather was the primary enemy in the area, not the Japanese.

The target of Bruun’s second operation was the railway at Paleik, south of Mandaley in Burma. In the days to follow, the crew practiced low-level attacks at night. This turned out to be in preparation for the next operation: an attack on the railway station at Hnohngpladuk in Siam. The aircraft reached the area easily, but Bruun had difficulties identifying the primary target. Instead the crew bombed the secondary target, a railway bridge over the river at Nakon Chai Si west of Bangkok; this target was attacked with good results and no flak was experienced. The return flight proved to be yet another long and hard flight. Carburettor trouble caused one engine to be feathered over the engines. The Liberator VI (EV155/B) returned to base after more than eleven hours in the air.

On 3–4 November 1944, the USAAF and RAF bombed targets in Rangoon. Bruun was part of the attack on the second day, where Liberators from 356, 215, and 355 Squadrons attacked the city. After bombing, the formation was attacked by ten Japanese Ki 43 and Ki 44 fighters. The air gunners returned fire, and the accompanying escort of nineteen P-38 Lighting and a total of fifty-four P-47 Thunderbolt fighters from both the RAF and USAAF prevented further attacks.[10] Bruun was in the air again on 13, 19, and 24 November 1944, bombing railway targets in Burma and Siam. In-between those dates, on 22 November, the squadron attacked the harbour and jetty area at Khao Huagang (Kao Huaking) at Kra Buri River, which forms the border between Burma and Siam. With more than 2,500 miles, the operation was the longest conducted in the Liberator at this stage of the war.[11]

For the next month, Bruun’s crew was withdrawn from operational service in order to recuperate and carry out a structured training program, with special focus on close formation flying. On 23 December 1944, Liberator Mk. VI KH115/X set course for Japanese stores in the area of Taungup. The mission was a repetition of a successful attack two days before, when aircraft from the Strategic Air Force had attacked the same target. This time around, seven aircraft from 356 Squadron participated. They formed over the Sunderbands, before flying to the target in a box of four aircraft and a vic three. Bruun’s crew was the fourth and final crew in the first group, and dropped bombs in formation. On 1, 4, and 11 January 1945, Bruun returned to attack railway targets in Burma and Siam. On the first of these sorties, they had to return early on three engines due to engine trouble.

Victory in Burma

At the Second Quebec Conference in September 1944, it had been decided to aim for an airborne and amphibious attack on Rangoon in March 1945 (Operation Dracula). Such an operation required the transfer of troops from Europe, which proved impossible in the end, and so a large offensive was carried out on central Burma (Operation Capital) instead. The plan was for the British Fourteenth Army to encircle the Japanese forces in the area around Mandalay, and to advance from this point towards Rangoon. At the same time, XV Corps was to advance along the coast in Arakan. Bruun was involved in the tactical support to these operations.

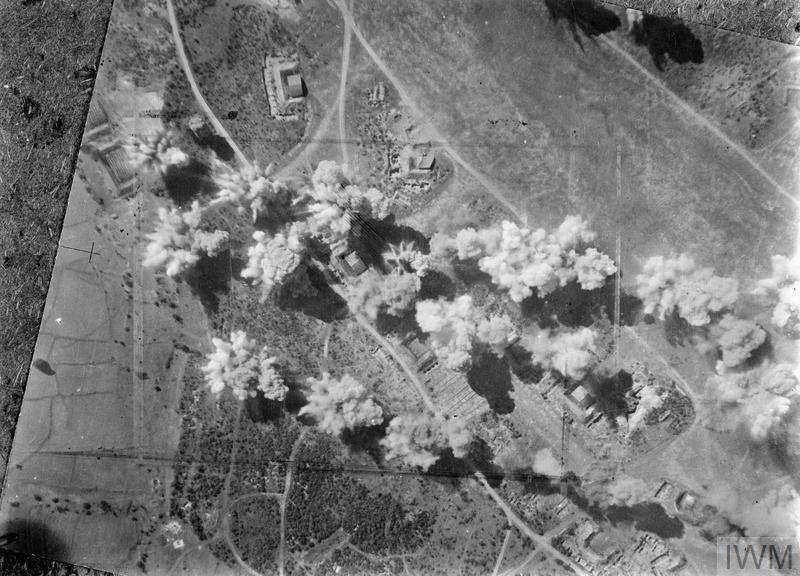

The 13 January 1945 attack on the military barracks in the Sappers Line, north of the moat in Mandalay (Area 3), was a fine example of this support. Fifty-four four-engined bombers were involved in the operation, including Bruun’s crew in Liberator Mk. VI KH354/F. The operation was successful. They were met by little flak, and the bombing was accurate. Reports stated that more than seventy buildings had been destroyed in the area, and up to 1,000 Japanese soldiers killed. The squadron did not only target ground forces. On 18 January 1945, seventy-two Liberators in close formation—escorted by Thunderbolt fighters from 134 and 258 Squadrons, RAF, and P-47s from the 1st Air Commando Group, USAAF—attacked the Kanguang (Kangaung) airfield near Meiktila.

Three days later, on the 21st, British forces landed on Ramree Island. Prior to the landing, enemy positions on the island were shelled from ships off the coast. Attacks from low-flying fighter-bombers followed, and finally fourteen Liberators from 356 Squadron bombed the island. Bruun was detailed to bomb Japanese positions at Black Hill on the island. The weather was good and the target easily identified; the bombs covered the entire eastern half of Black Hill. Further operations were carried out towards the end of January.

On the 25th, the target was railway and industrial installations at Amarapura, south of Mandalay, and three days later the squadron targeted Japanese positions at Kangaw in support of the army’s advance on Myebon peninsula.

Bruun’s first operation in February was a night operation against railway installations at Jump Horn (Chumphon) in Siam, which involved almost fifteen hours in the air. On 11 February 1945, Bruun participated in the largest operation in Burma to date: the target was the northern half of the Dump ‘F’ at Rangoon. The operation was Bruun’s first on Rangoon. Eighty-four Liberators from RAF and USAAF and fifty-nine B-29 Superfortress made up the bomber force, which was escorted by thirty-six P-47 Thunderbolts from the RAF and eighteen P-38 Lighting from the USAAF.[12] The squadron bombed in formation from 10,300 feet and reported that the target area was covered by a good bomb pattern, although detailed observation was made difficult by the smoke from the ground. Shortly afterwards, six Kawasaki Ki 61 Hien (nicknamed ‘Tony’) scrambled from a nearby airbase to attack the Liberator (KH161/V).[13] The air gunner fired a deterrent burst, and the fighters broke away without attacking. The formation experienced intense and accurate flak; several aircraft were slightly damaged, but there were no injuries. The attacks against the Japanese forces in Burma and Siam continued through February and March. One of the objectives of the heavy bomber squadrons during these months was the systematic destruction of the enemy dumps, mainly dispersed in the Rangoon area.[14]

Bruun did not take part in operations during the first three weeks of April. On 23 April 1945, he returned to operations, the target being Dump No. 1 in Rangoon (Area A). At this point in time, the Fourteenth Army were advancing rapidly through Burma. The original order for the operation was to attack the outskirts of Toungoo to support the advance of the army, but a thunderstorm delayed the operation twenty-four hours. By then, British tanks had reached the town, and plans were changed—instead, the squadron bombed the target from 11,000 feet in close formation. Several of the aircraft experienced bombing gear failure, which was believed to be caused by the severe thunderstorm and heavy rain the night before the operation.

On 1 May 1945, the squadron returned to Rangoon. This was to be Bruun’s last operation before leaving Burma. This operation was carried out on the night before the recapture of Rangoon (Operation Dracula). The other heavy bomber squadrons had been assigned to take part in the operation. The previous day, twelve aircraft had been briefed to bomb gun positions on Elephant Point on the flat plain south-west of Rangoon. Paratroops had been dropped at this location in the early hours of the morning, encountering no resistance in the drop zone. The airborne troops had advanced about two and a half miles towards Elephant Point and were now waiting a larger formation of Liberators to soften the enemy positions. Stringer-Jones took off from Salbani in Liberator KH115/X at 0435 hrs. The twelve Liberators proceeded to the target in gaggle. Bruun released a single stick over the target (position ‘C’) at 1014 hrs; the stick fell east of the target on the edge of the river. On the return journey, the crew landed on the recently liberated Ramree Island owing to heavy weather. They had been in the air for eleven and a half hours, and had nearly exhausted all fuel.

By then, Bruun had completed his first tour of operations, or approximately 300 hours of operational service. At the same time, the last Japanese troops left Burma. He was thus enjoying the liberation of Burma, as well as that of Denmark during the following days.

Returning Home

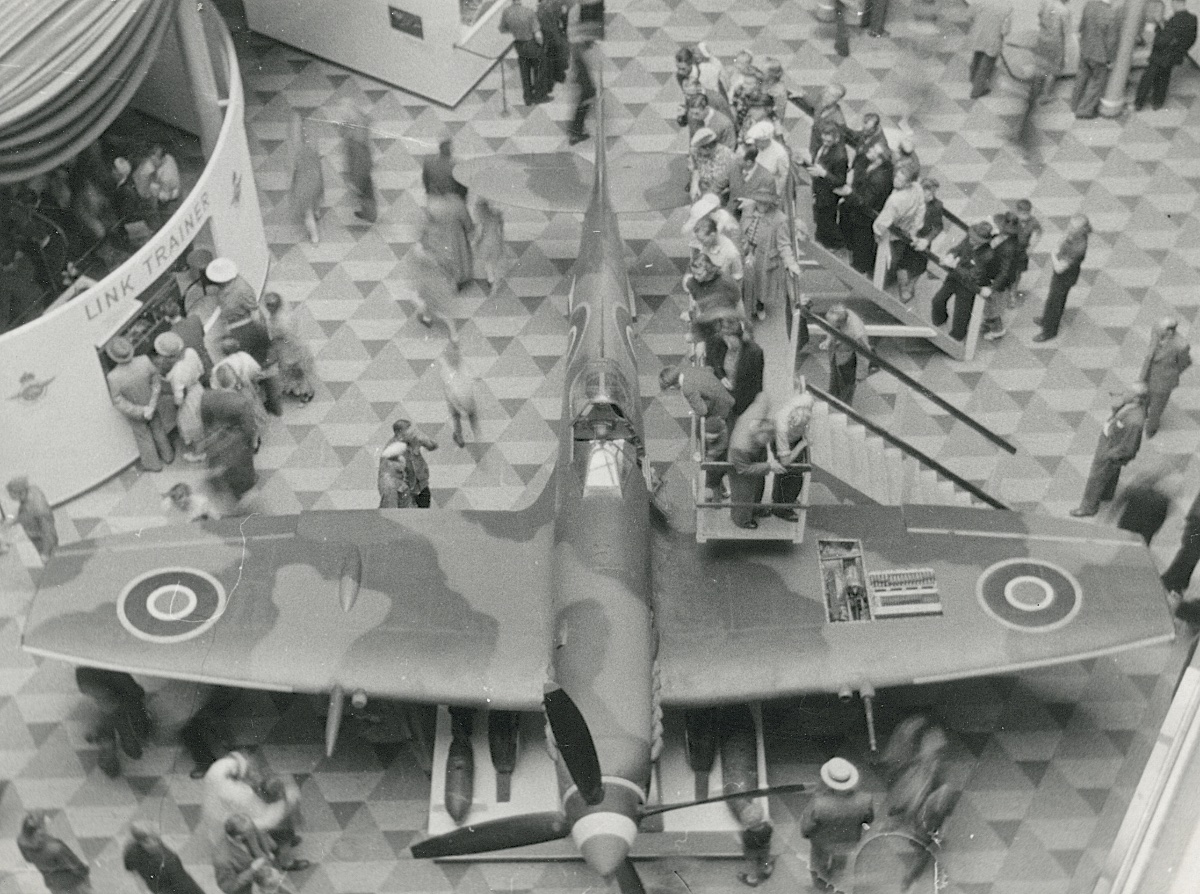

Bruun was to leave Burma in June 1945, but his departure came sooner than expected. His former employer, the department store Magasin du Nord in Copenhagen, had been chosen to host a Royal Air Force Exhibition and had asked for Bruun to be released to assist. The exhibition opened on 23 June 1945.

He was supposed to leave Bombay by ship at the end of June. Instead, he returned from Calcutta—via Karachi, Shaibar, Cairo, Malta, and London—to Copenhagen, arriving on 28 June 1945.

Bruun followed the exhibition as it moved to Aarhus, where it opened on 15 August 1945 and, later, as it continued to the Norwegian capital, in Glasmagasinet in Oslo. He met his future wife at a dinner party during the Aarhus exhibition. He swopped his place at the table with a high ranking RAF officer for a carton of cigarettes and, by chance, he became seated next to her. They married in March 1946, a month after he was released from service. Bruun returned to Magasin du Nord and later became managing director of the renowned men’s department store Brødrene Andersen in Copenhagen.[15]

Endnotes

[1] DNA: Parish register, Solbjerg Sogn.

[2] Bruun, unpublished manuscript for presentation at Rotaty, 1989 (DAHS).

[3] Bruun, unpublished manuscript for presentation at Rotaty, 1989 (DAHS).

[4] FHM: 15A-20929-1, interview with Jørgen Bruun.

[5] Probert, The Forgotten Air Force (1995), pp. 204–209.

[6] NA: AIR 27/1758–59. If nothing else is stated, the information on 356 Sqn operations is based on this source.

[7] Bruun, manuscript for presentation at Rotary, 1989 (DAHS).

[8] Gwynne-Timothy, Burma Liberators (1991), pp. 743–744.

[9] Bruun, manuscript for presentation at Rotary, 1989 (DAHS).

[10] Shores, Bloody Shambles, Vol. 3 (2005), pp. 279–80.

[11] ibid., p. 286.

[12] ibid., p. 328.

[13] ibid., p. 325.

[14] Park, Despatch on Air Operations in South-East Asia (1951), p. 1982.

[15] Bruun, manuscript for presentation at Rotary, 1989 (DAHS).